Background

For the past week or so, I have spent significant amount of my time on creating an auto solver for ctf challenges based on radius2, a symbolic execution framework written in rust. It was a great excuse for me to learn more in depth about rust and its ecosystem. So far, I was able to automatically solve anything in the range of 100~200 points.

This was great and all but as much as I was happy to learn about rust, I was more interested in how to efficiently reverse the binary written in rust because it is not uncommon to see one in the ctf scene. So I took a break from tool development and searched through online for any challenges written in rust (suitable for practice) and luckily found one in this year defcon. The name of the challenge is blackbox and this is a quick write up for it.

Building

No instruction so I guess this was (?) the build instruction:

1

2

3

git clone https://github.com/Nautilus-Institute/quals-2023.git

cd blackbox

cargo build --release

It is possible that the binary was actually stripped via cargo-strip but I did not see any sign of it in the file Carog.toml.

Binary

As an initial test, I fed in various input data to the challenge to observe its response:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

➜ file blackbox

blackbox: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, BuildID[sha1]=d30d9872e3351bad2630360997d8c64da197fdb5, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, with debug_info, not stripped

➜ ./blackbox

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Program too large!

# Testing various input as a starter

➜ print -P '%F{118}\u2586%f' | ./blackbox

Program too large!

➜ python -c 'import string;print(string.printable)' | ./blackbox

Program too large!

➜ echo "\x41\x41" | ./blackbox

Program too large!

➜ echo "\x05\x05" | ./blackbox

Program too large!

➜ echo "\x05\x01" | ./blackbox

thread 'main' panicked at 'called `Result::unwrap()` on an `Err` value: Error { kind: UnexpectedEof, message: "failed to fi

ll whole buffer" }', src/main.rs:383:42

note: run with `RUST_BACKTRACE=1` environment variable to display a backtrace

➜ echo "\x01\x00\x41\x41" | ./blackbox

Execution halted!

A: 0 B: 0 C: 0 D: 0: PC: 1 SP: 0

Would you like to start over? (y/n)

Based on its output and error, it seems this program is a some form of cpu emulator which accepts the data in the form of length:data.

Analysis

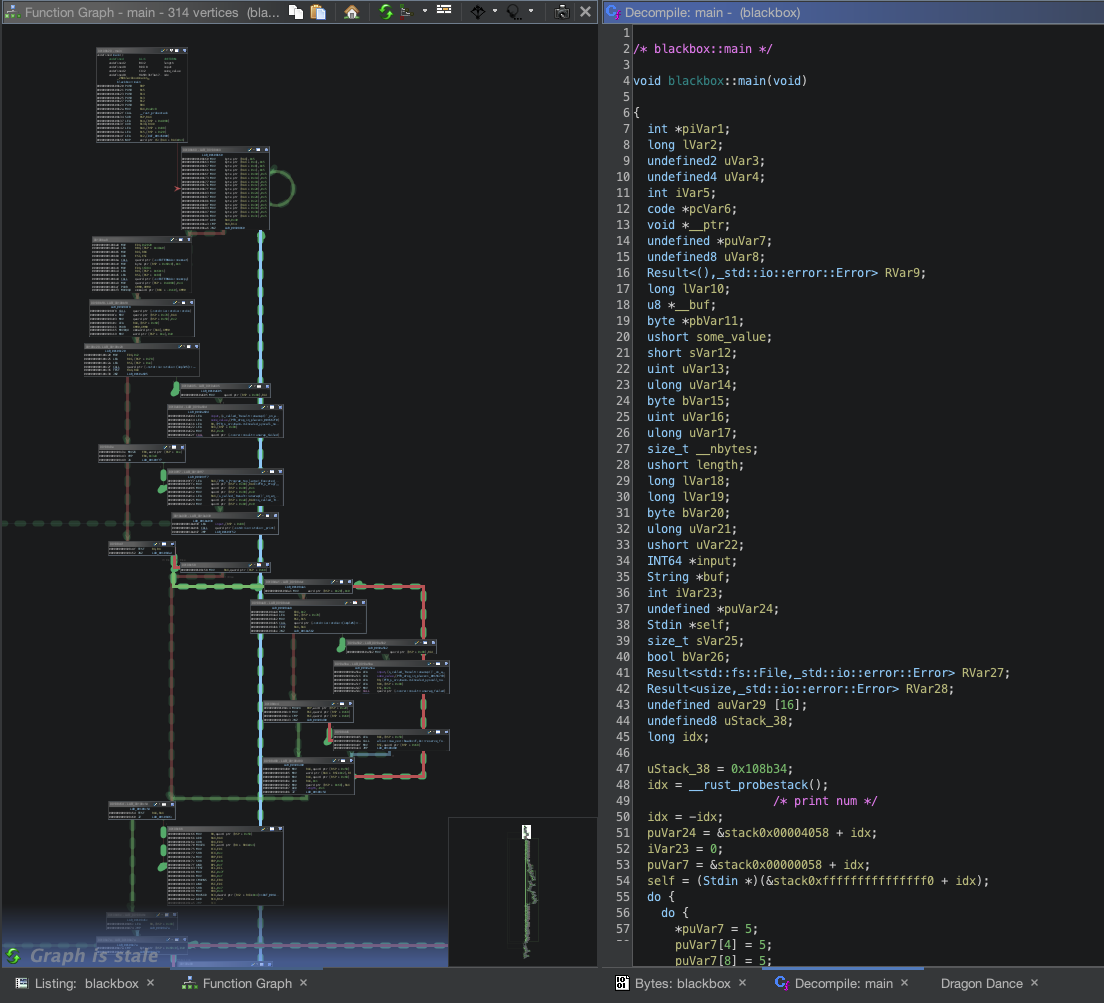

This challenge was written in rust which is known to produce a super messy decompiler ouput. This is what its main function looks like in Ghidra:

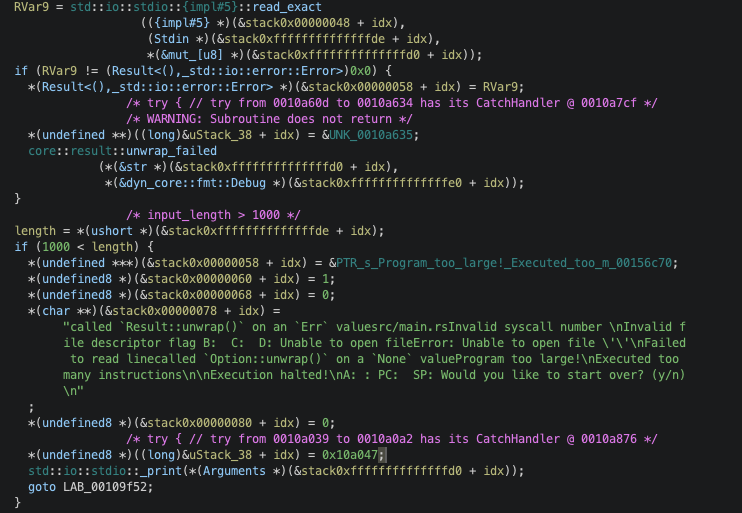

The main function is somewhat unpleasant to read but it is not as bad as I would have thought because it at least prints something out to stdout. This made a bit easier to track my input and referenced strings in the decompiler output. The first and most obvious thing to look for was a string “Program too large!”:

It checks if the input is greater than 1000 and exits if it is with an error message. The key here is the input read from read_exact is casted to ushort which is 2 bytes (16 bit). This explains why my input 0x0105 (261 in decimal) worked but 0x0505 (1285) did not.

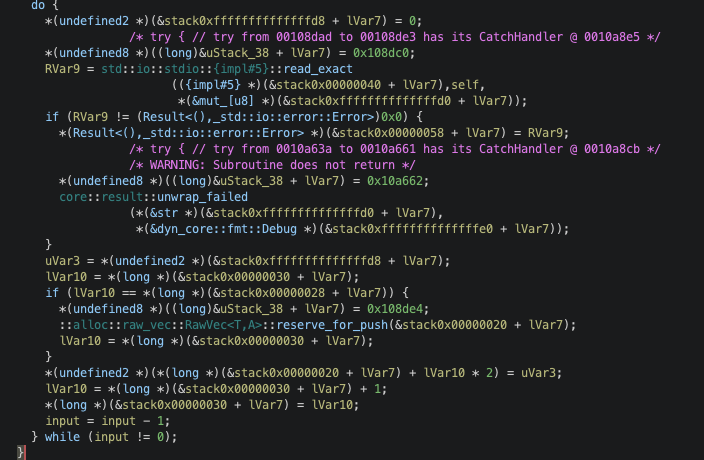

After reading the input length, it reads the length amount of data and push to some vector:

It was not clear what the size of u8 byte array was but checking it under a debugger showed it was reading 2 bytes at a time. This makes it total of 2000 bytes (1000 * 2) of data to work with for instructions.

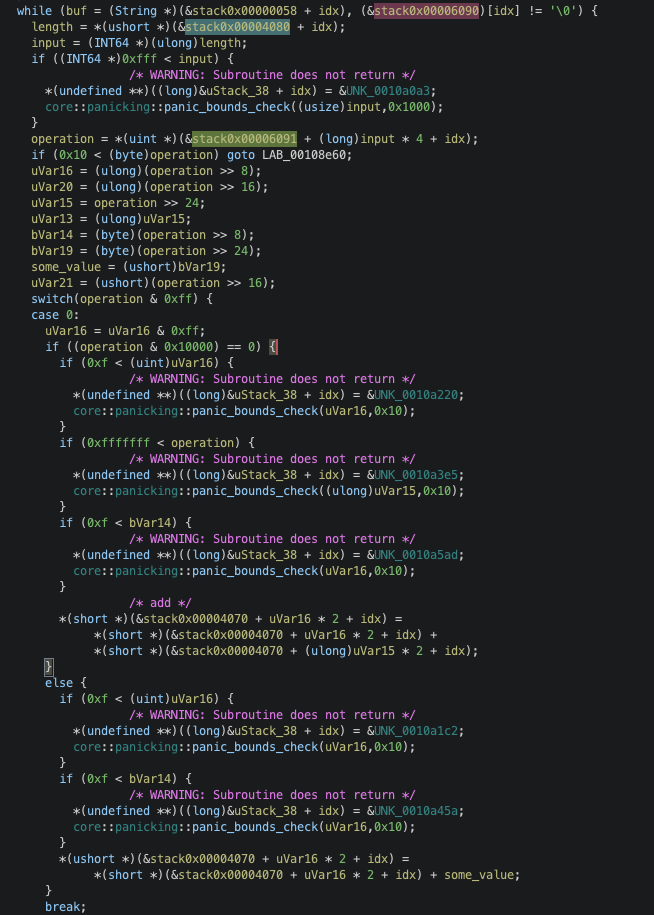

Once the vector is filled with some bytes, it performs some operations on those and checked its value to run various instructions:

This is a long switch case but it can be easily summarized as following pseudocode:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

switch(operation & 0xFF){

case 0:

"add" some value

break;

case 1:

"subtract" some value

break;

case 2:

"load" some value

break;

case 3:

"store" some value

break;

case 4:

?

break;

case 5:

jmp to panic for too many instructions

break;

case 6:

"and" some value

break;

case 7:

"or" some value

break;

case 8:

"xor" some value

break;

case 9:

"not" some value

break;

case 10:

"shl" some value

break;

case 11:

"shr" some value

break;

case 12:

? some value

break;

case 13:

"push" some value

break;

case 14:

"pop" some value

break;

case 15:

? some value

break;

case 16:

? some value

break;

}

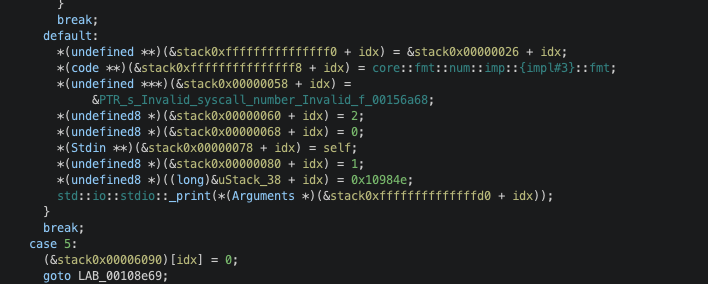

case 4 which I marked with ? also has a switch case that performs some operations. At first, I did not know what it was but one of the error strings showed it was for syscall:

There are six syscalls and the equivalent pseudocode is something like the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

sysnumber = mem[idx];

switch(sysnumber){

case 0:

exit

break;

case 1:

print number

break;

case 2:

print string?char?

break;

case 3:

get string?char?

break;

case 4:

open file

break;

case 5:

read file

break;

default:

panic("Unknown Syscall");

break;

}

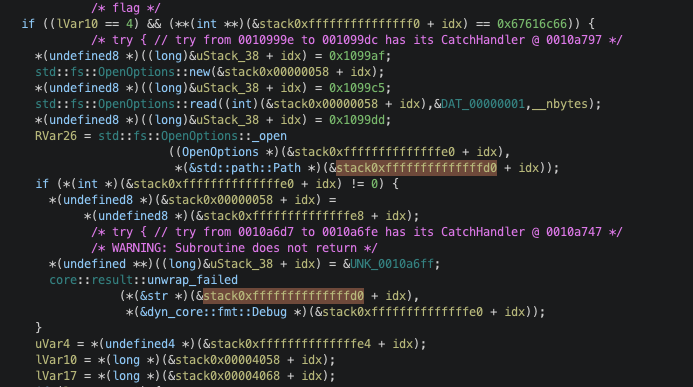

Looking through its available syscalls, I found one interesting check in open file:

It opens the file only if the input memory region (stack?) has a value of 0x67616c66 which is equivalent to string flag. This makes it clear that the end goal is to create a shellcode that opens and reads the flag and somehow prints it out to stdout.

Solution

Before I created a solution script, I wrote down what I have found:

- There are six registers

A,B,C,D,PC,SP - There are six syscalls

- There are twelve

usableinstructions - Only allow up to

2000bytes (or1000instructions) - Instruction is 16 bit

- Have to make a syscall for opening and reading a file

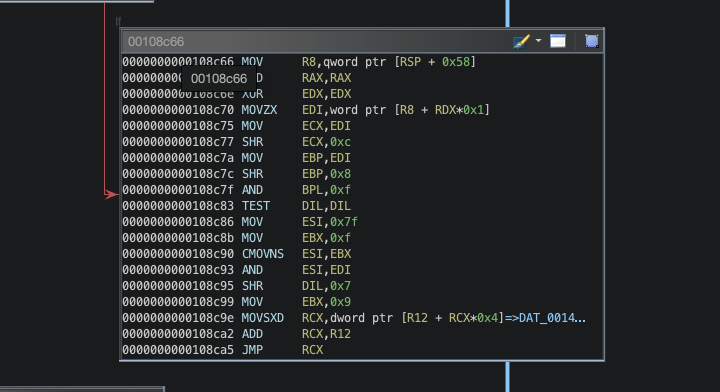

Based on the above information, I traced/re-visited what operations are performed on my input and this was where I spent a bit of time on because I did not realize the decompiled ouput from Ghidra was not correct. Eventually, I used a debugger and looked at its disassembly output and found the calculation routine at offset 0x8c66:

The actual calculation is very simple and the following is the equivalent pseudocode (for things that I was interested in):

1

2

3

ops = (input >> 12) & 0xF

dst = (input >> 8) & 0xF

src = (input & 0xFF)

This allowed me to generate bytes to execute various instructions I wanted but I still needed to figure out how registers get used for syscalls. To test this out, I generated various payload to make a syscall and observe the value of each reigster and this is what I have found:

- Register

Aseems to be used as a syscall number - Register

Bseems to be used as an argument1 - Register

Cseems to be used as an argument2 - Register

Dseems to be used as an argument3

In addition, it was found print syscall allows to print a character (thought it was for string) or a number (16 bit) so have to print a flag one or two bytes at a time.

I decided to print a character at a time and this is what I came up with to print out the full string:

- Set register

Ato3viaadd - Write

flagone character at a time to a stack via syscall - Write

0which is a stack address that points to ourflagstring to registerB - Increment register

Aby one viaadd - Call

opensyscall - Increment register

Aby one viaadd - Move

fdto registerB(turns out I did not have to do this) - Set register

Cto a stack address - Set register

Dto a relative big value (used as a length) - Call

read_filesyscall - Subtract

3from registerAviasub - Load one byte at a time from a stack to register

Band print it to stdout viaprint_char

I used z3 to generate all the necessary bytes and this is the end result:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

➜ python blackbox_solver.py

Instrs Length:526,Payload Length:1052

[+] Starting local process './blackbox': pid 27757

[*] Switching to interactive mode

f\x00\x00ccc\x00ccccccf\x00\x00ccc\x00ccccccf\x00\x00ccc\x00ccccccf\x00\x00ccc\x00ccccccf\x00\x00ccc\x00ccccccf\x00\x00ccc\x00ccccccf\x00\x00ccc\x00ccccccf\x00\x00ccc\x00ccccccctf{this_is_for_a_test}

\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00Execution halted!

A: 2 B: 0 C: 0 D: 127: PC: 526 SP: 4

Would you like to start over? (y/n)

$ n

[*] Got EOF while reading in interactive

[*] Process './blackbox' stopped with exit code 0 (pid 27757)

[*] Got EOF while sending in interactive

➜ cat flag

ctf{this_is_for_a_test}

Here is the solver:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

from pwn import *

import z3

#context.log_level = True

class REG:

a = 0

b = 1

c = 2

d = 3

pc = 8

sp = 9

class Op:

add = 0

sub = 1

ldr = 2

st = 3

sand = 4

sor = 5

xor = 6

snot = 7

shl = 8

shr = 9

jmp = 10

what = 11

how = 12

push = 13

pop = 14

sys = 15

class Sys:

exits = 0

prints = 1

print_char = 2

get_char = 3

open_file = 4

read_file = 5

def solver(opcode,dst,src) -> int:

op = z3.BitVec("op",16)

s = z3.Solver()

s.add(((op >> 12) & 0xF) == opcode) #sr

s.add((((op >> 8) & 0xF) & 0xFF) == dst) #dst

s.add((op & 0xFF) == src) #dst

if s.check():

m = s.model()[op].as_long()

return m

return 0

payload = b""

# SET REG A Syscall number

payload += p16(solver(Op.add,REG.a,0x83))

# PUSH 0x66 (f)

payload += p16(solver(Op.sys,0,Sys.get_char))

payload += p16(solver(Op.push,0,REG.b))

# PUSH 0x6c (l)

payload += p16(solver(Op.sys,0,Sys.get_char))

payload += p16(solver(Op.push,0,REG.b))

# PUSH 0x61 (a)

payload += p16(solver(Op.sys,0,Sys.get_char))

payload += p16(solver(Op.push,0,REG.b))

# PUSH 0x67 (g)

payload += p16(solver(Op.sys,0,Sys.get_char))

payload += p16(solver(Op.push,0,REG.b))

# call open

payload += p16(solver(Op.sys,0,Sys.get_char))

payload += p16(solver(Op.add,REG.a,0x81))

payload += p16(solver(Op.sys,0,0))

# set length

payload += p16(solver(Op.add,REG.d,0xFF))

# read file

payload += p16(solver(Op.add,REG.a,0x81))

payload += p16(solver(Op.sys,0,0))

payload += p16(solver(Op.sub,REG.a,0x83))

# guess the length

for i in range(0xFF):

payload += p16(solver(Op.ldr,REG.b,i))

payload += p16(solver(Op.sys,0,0))

l = (len(payload)//2)

print(f"Instrs Length:{l},Payload Length:{len(payload)}")

r = process("./blackbox")

#pause()

sl = r.sendline

sn = r.send

sn(p16(l))

sn(payload)

# push to stack

sl(b"f")

sl(b"l")

sl(b"a")

sl(b"g")

# stack address

sl(p16(0x0))

r.interactive()

Conclusion

This was a fun challenge to tackle on and such a good reminder of why reading the disassembly output is important when it comes to rust binary in Ghidra. In the next post, I will discuss some of techniques/struggles to make rust reversing more pleasant.